Out of the darkness of the background appear pairs of figures—pale, finely drawn, seemingly coming from mythical narratives—on two horizontal wall hangings. These flank a narrow, deep, windowless basement room richly embellished with the very tapestries made of paper painted by the artist. It is a ritualistic-looking shrine, big enough to walk into, and decorated in a strict symmetry with amulets, figurines, and lamps; in the middle a person sits enthroned. He wears a painted suit fitted with feathers, evil-eye amulets, and strands of raffia, and he puffs periodically on a nargila, the Croatian word for hookah, which was designed by the artist.

The base of the hookah is the same sort of clay figure that is seen depicted on the rear wall and is similar to a pre-Columbian statue. The man, a sort of cultic leader, appears to be completely concentrated on this very minimal activity. Typical for Vered Koren, her pictorial world created through painting, showing dancers and riders, landscape scenes, shrines and temples on paper goblens, Croatian for tapestries, which she often also shows alongside video installation, generates a fantastical world steeped in history before our eyes. The title of the tapestry refers to Grand Rabbi Yeshaya Steiner, an influential rabbi who lived in the 19th century in the then Hungarian village Kesterir, where his grave is a pilgrimage site to this day for thousands of Hasidic Jews. Great healing powers are ascribed to Rabbi Steiner and his image is today venerated like a protective amulet.

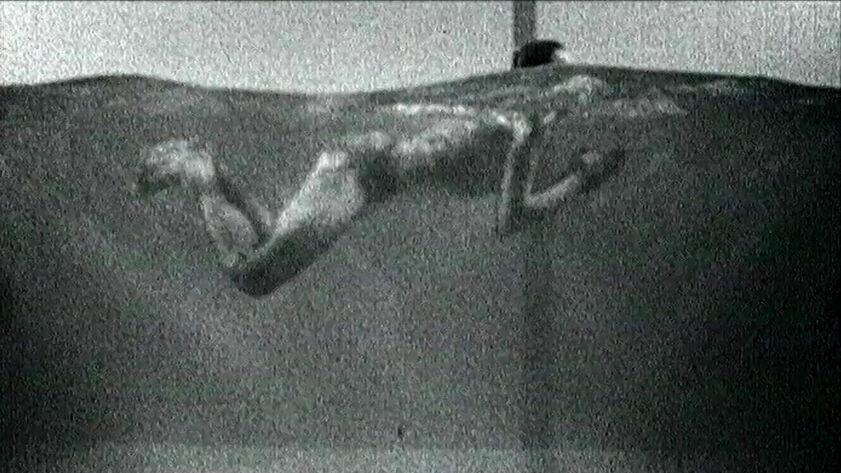

With this, the first sequence of Koren’s video installation Firestarter, from 2017, transports us into a richly visual world, one that invokes different religious faiths, cults, narratives, and folk tales and is shown on three screens, positioned close to each other and somewhat higher than the line of sight, in the black box exhibition space at Glasmoog. The only sound is a long-drawn-out rhythmic bubbling spreading throughout the space. It is briefly interrupted by an at first inaudible yet visible exhalation of water vapor, before it begins again. This gives way in the pauses to the sounds of the wind, which play in the hanging fabric panels and pennants in the shrine room, and later in the evil-eye talismans that hang in the burnt and barren branches in the landscape. The clinking of the evil-eye amulets made of blue-colored glass is, along with the wind, the basis of the sounds of the wide landscape near Haifa in Israel, empty of people except for the bearded protagonist. The barrenness of the mountainous area is contradicted by the closeup views of the inhalations and exhalations of the hookah-smoking, shaman-like man, whose hairy chest is just as artistically decorated with drawings as his painted suit jacket, which finds its floral counterpart in the withered bushes and featherlike palm fronds in the surroundings. In the juxtaposition of distant and close views, the protagonist sometimes appears searching about in the landscape, tossing charred branches atop a pile as if arranging it as a fire pit. But he is able only to pile it with stones and amulets and in parallel rely on the rhythmic inhalation and exhalation of the hookah. It remains to be seen if the shaman, the rabbi, or the religious leader is able to arm the landscape against further natural catastrophes; the abundant use of evil-eye nazar amulets, which seem to stare back at us, are more suggestive of a human need for protection than the persuasive powers of a ritual.

The desert landscape we see is permanently damaged, etched by large-scale wildfires, which due to the dry climate and high winds raged dramatically for several days in and around Haifa and led to the evacuation of 60,000 people. More than 100 people were treated in the hospital for burns and smoke inhalation, as summarized by the report of the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre. The title Firestarter suggests however the opposite: here the artist refers to the statements of elected officials, and partly journalists, that speculated arson and terror attacks were behind these climate-related fires. Due to this discrepancy, they soon faced accusations of spreading fake news as there was no evidence for their version of the story.

The skillful weaving together and contrasting of these worlds—one marked by environmental catastrophes and concentrated on rituals, a post-apocalyptic outer world that escapes our control and a fatalistic inner one oriented toward everyday beliefs and relying on myths, a world in which systems shall continue to persist through symmetries and rituals—forms an interval, an optical illusion. With this and her subtle humor (e.g., the water vapor countering the already scorched nature), Koren directs our attention to exactly this intermediate space, this temporal interval in which the protagonist is poised, and between which we move visually, conceptually, and spatially back and forth.

Text - Lilian Haberer

Vered Koren, born in 1985 in the kibbutz Kfar Masaryk in Israel, lives and works in Cologne and Tel Aviv.

Education

From 2016 Academy of Media Arts Cologne, postgraduate program

2007–2011 Hamidrasha Faculty of the Arts, Beit Berl College, B.Ed.F.A. with honors—Interdisciplinary Art and Art Education

Solo Exhibitions

2019 Segulot, Labor Ebertplatz, Cologne

2018 Urban Legends, Skola6 Art Space, Cesis, Latvia

2016 Treasure Hunters, online exhibition for the magazine Erev Rav, Israel

2015 WitchCraft, Museum of Israeli Art, Ramat Gan, Israel

2015 Black Magic, Shangyuan Art Museum, Beijing, China